Once upon a time, a little white girl found Bad Feminist in a bookstore in Aspen. Yes, Aspen. A very white place, and not because of the snow.

She had just learned that feminism wasn’t a bad thing in Dr. Julie Steward’s literary theory class, a class that increased her empathy by at least 15%.

If the church taught literary theory, she thought, Christians would be actually empathetic and much less defensive.

Simultaneously, someone decided that Christians should fight critical race theory with a well-organized moral panic. The dusty ideas that had sat peacefully in English classrooms since the seventies were pulled into sermons and labeled as the next weapon of Destroying All Things Right and Good.

She was me, and I was confused.

At that time I did not have this Substack, with its many millions of followers, nor did I have another platform or griddle on which to roast this strange and disturbing development.

But thankfully, earlier that year, I had found Bad Feminist. I had read it. I had received my bullshit immunization.

Writing is powerful and reading is powerful.

Marginalized people are kept from power: oppression.

Oppressors have always controlled writing and reading as a crucial way to hoard power.

Thus the act of writing as a marginalized person is powerful. Thus reading books written by marginalized people is a privilege.

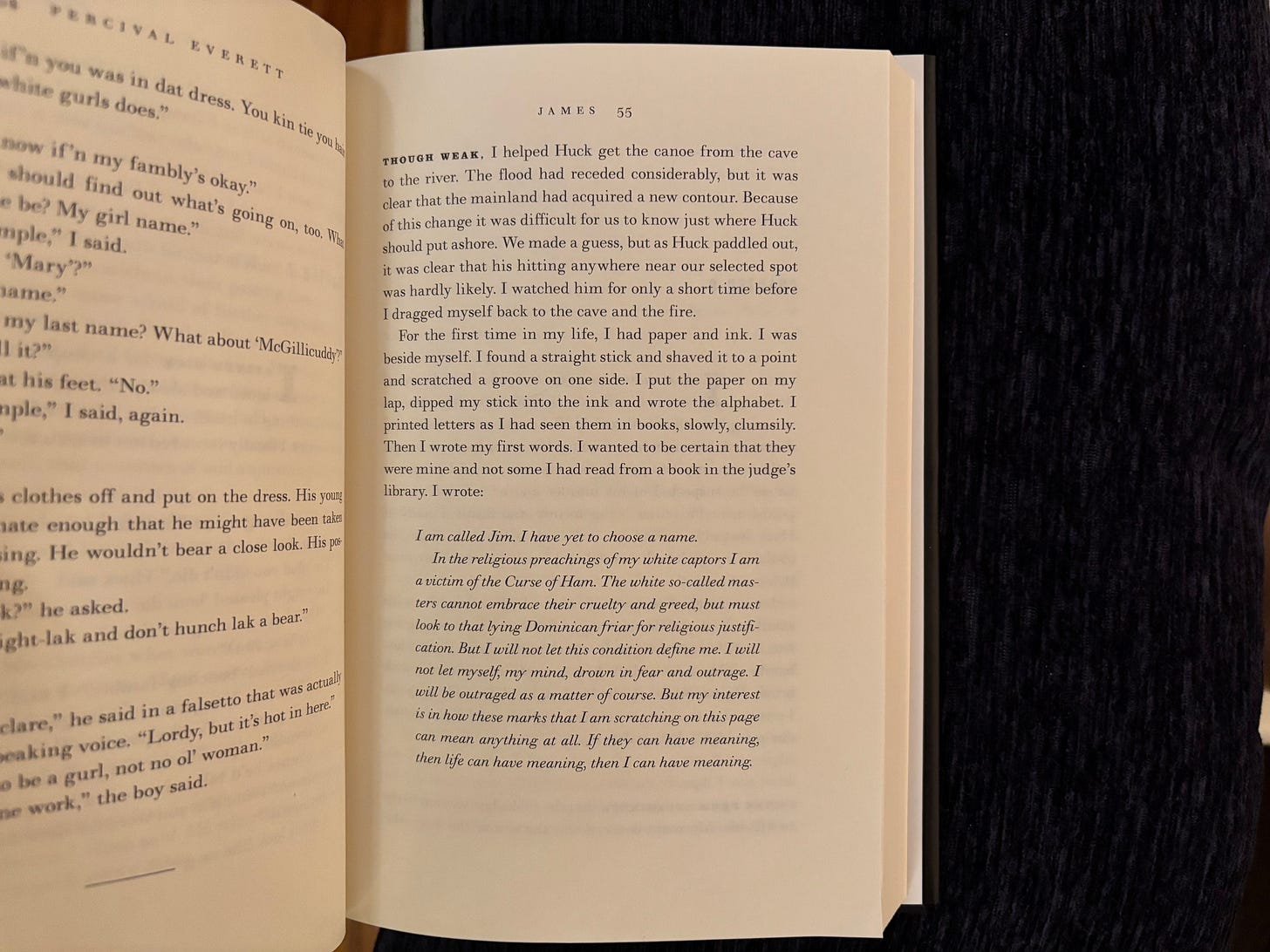

It is no mistake that James, which at its top level tells the story of the slave who fled with Huckleberry Finn, is at a deeper level a novel about exercising authorship. To write is to study the most interesting parts of your own mind, and to publish your writing is to share your most powerful thoughts at scale.

<>

To write is to study the most interesting parts of your own mind, and to publish is to share your thoughts in their most persuasive form at scale.

<>

To write is to study the most interesting parts of your own mind, to edit is to shape your messy thoughts into their most persuasive form, and to publish is to share at scale. And though there is power in each step, it’s publication that allows one person’s thoughts to reach thousands of people. Publishing preserves thoughts, so you can read something written by someone long dead, which makes reading a kind of time travel.

And traveling back to 2016, in that bookstore in Aspen, I bought Bad Feminist, and it changed my life.

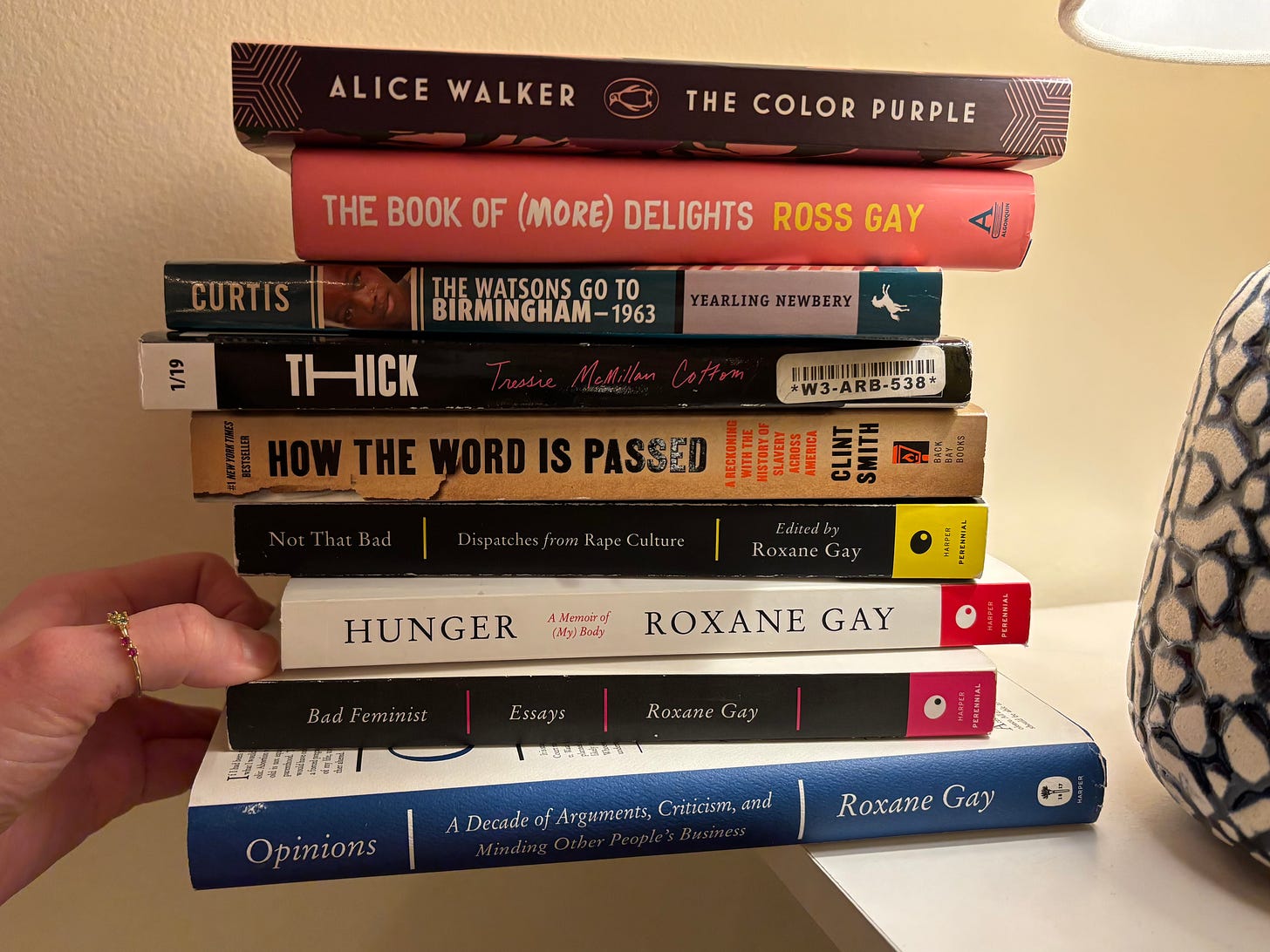

So you must start with Bad Feminist. Even though it came out ten years ago. Even though there’s many other, more recent, essay collections you want to read. You must start with Bad Feminist, because all the essay collections since Bad Feminist were created in reference and debt to Bad Feminist. Roxane Gay wrote about the intersectional experience of being Black, female, and queer in the United States. She wrote about violence and gender and pop culture and power. She wrote fifteen paragraphs about Orange is the New Black that are a stronger seed of wisdom and nuance than the entire self-help section of a suburban Barnes & Noble.

There are parts of my mind and my wisdom that are inextricable from what I learned in Bad Feminist. So that is where you will start. And once you finish, if you want Roxane Gay’s commentary on more recent happenings, Opinions is there for you. If you want Roxane Gay to compile 29 essays by other writers about rape culture, Not That Bad is there for you. But Bad Feminist is where you must start.

After Bad Feminist, you will read Hunger. Not immediately after. That may destroy you. But you will read Hunger after, certainly.

The first time I read Hunger I wasn’t someone who bought books for myself. I didn’t know why independent bookstores mattered. The first time I read Hunger, I was visiting my older sister, and I pulled it off the shelf and started. After my second or third visit reading what I could while I was there, I left a bookmark in my spot. The book was destroying me and rebuilding me and I read it one hammer, one brick at a time.

I cannot tell you anything about Hunger. Except that it is required.

In case you’re in the mood for fiction now, I’ll jump to a middle grade book. I saw this book had “Birmingham” in the title and a Newberry Honor medal on the cover and I snatched it to the top of my TBR.

It’s The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963.

Turns out, it’s delightful. Kenny is the middle child, and his sibling relationships feel real, from bickering to cookie-throwing to saving each others’ lives. There’s character transformation in every chapter, starting with Kenny making a friend, continuing through a serious talk with his dad and running around with his older brother. These small pieces of growth work together so that the ~event~ in Birmingham feels totally earned. Remarkable.

We’ll stay in fiction, but we’ll return to the themes we encountered in Roxane Gay’s work—race, gender, violence, and growth. Meet The Color Purple.

I knew nothing about this book before starting it. The movie was about to come out and I knew it was a classic so I read it. Alice Walker’s mastery of the craft of writing is at the level where you’re convinced she was born with the ability to print perfection straight out of her brain on the first try. Like. Logically I know she has to “try” and “edit” and put forth “effort,” but when I’m reading it, it feels effortless.

The novel is epistolary. Like James, The Color Purple is another book that explores the importance of authorship. Letters are a way to share a specific sentiment with a specific person; in The Color Purple, Celie writes the letters to God and then switches and begins writing them to a character. The book stares unflinchingly at violence, but every bit is shunted down lovingly-designed paths towards character transformation and, dare I say, redemption. It’s like the ocean, or a shooting star: it must be experienced to be believed.

Back to nonfiction!

Clint Smith is another Black author who controls both individual words and overall structure with incredible finesse. In How the Word is Passed, he studies how slavery is remembered today at seven places where slavery happened in the past. The structure is simple—one location per chapter. Then, a few chapters in, I realized that his supplemental research moved chronologically, a second level of scaffolding strengthening his text. I can only imagine how much work went into the writing’s tone—he talked about how he felt in so many heavy moments, but never let indignation dominate the logic or feel of the writing. His tone was curious, gentle, and the work was stronger for it. I was so impressed for so many reasons.

Next, buy anything by Ross Gay. He’s a friend of Clint Smith, for what it’s worth. I read A Book of (More) Delights, which was precious and sharp and perfect. Gay wrote down things that delighted him every day for a year. Then he only used 81 for the book, which I found surprising and very clever. This process of selection, I’m sure, enabled my second surprise: each delight goes somewhere, it “essays” in the original sense of the word. He writes deeply into the everyday, deep enough to find the profound, the connection between one thing and everything else. His poet’s discipline in selecting detail shines through—each scene is bright and each digression trimmed (or lengthened!) perfectly. There’s lots of run-on sentences, which only sometimes got confusing—rarely enough that I was happy to blame myself and push through. Ha.

Lastly, for now, is Thick. First you ought to read this article, which wasn’t included in the book for some unknown reason. Then you may read. And read. And photograph multiple pages because you are on a plane and forgot your pencil. Not to brag, but my copy is an ARC (advanced reader copy), which Megan found and gave to me before I knew who Tressie McMillan Cottom even was. Before I knew she was best friends with Roxane Gay. It’s an icon, an artifact, and it’s all mine.

My two favorite essays from this are “In the Name of Beauty” and “The Price of Fabulousness.” I cannot say anything else because if I open the book I won’t put it back down, which happened earlier when I was writing about Hunger. Actually, let’s trade: I send you this article, and then I get to go open Thick and not close it.

It’s January 31st. Your TBR is now stacked.

“actually empathetic”

this is so good mah!