There’s a kids book that I found at the bookstore. It’s called All the Ways To Be Smart.

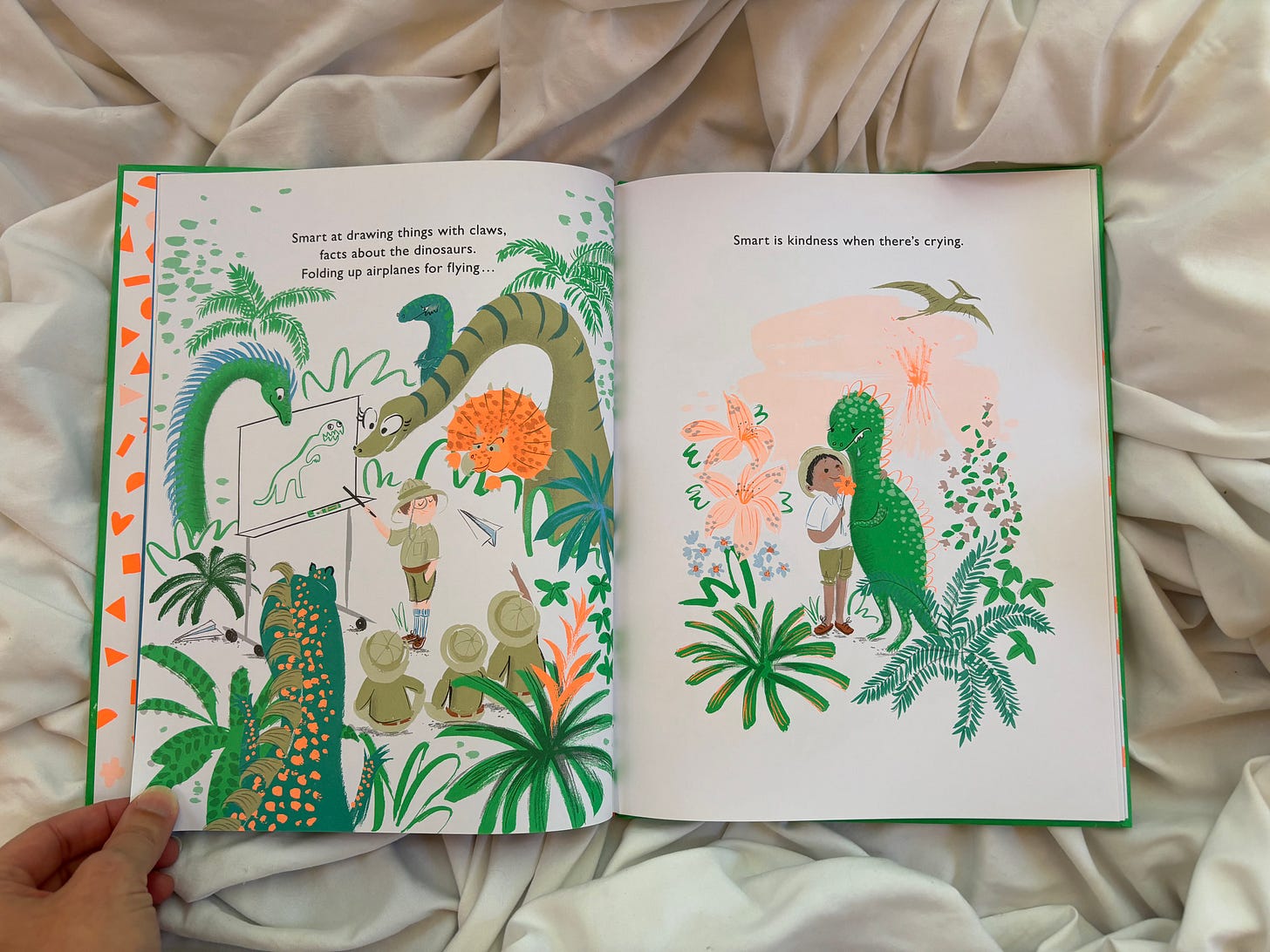

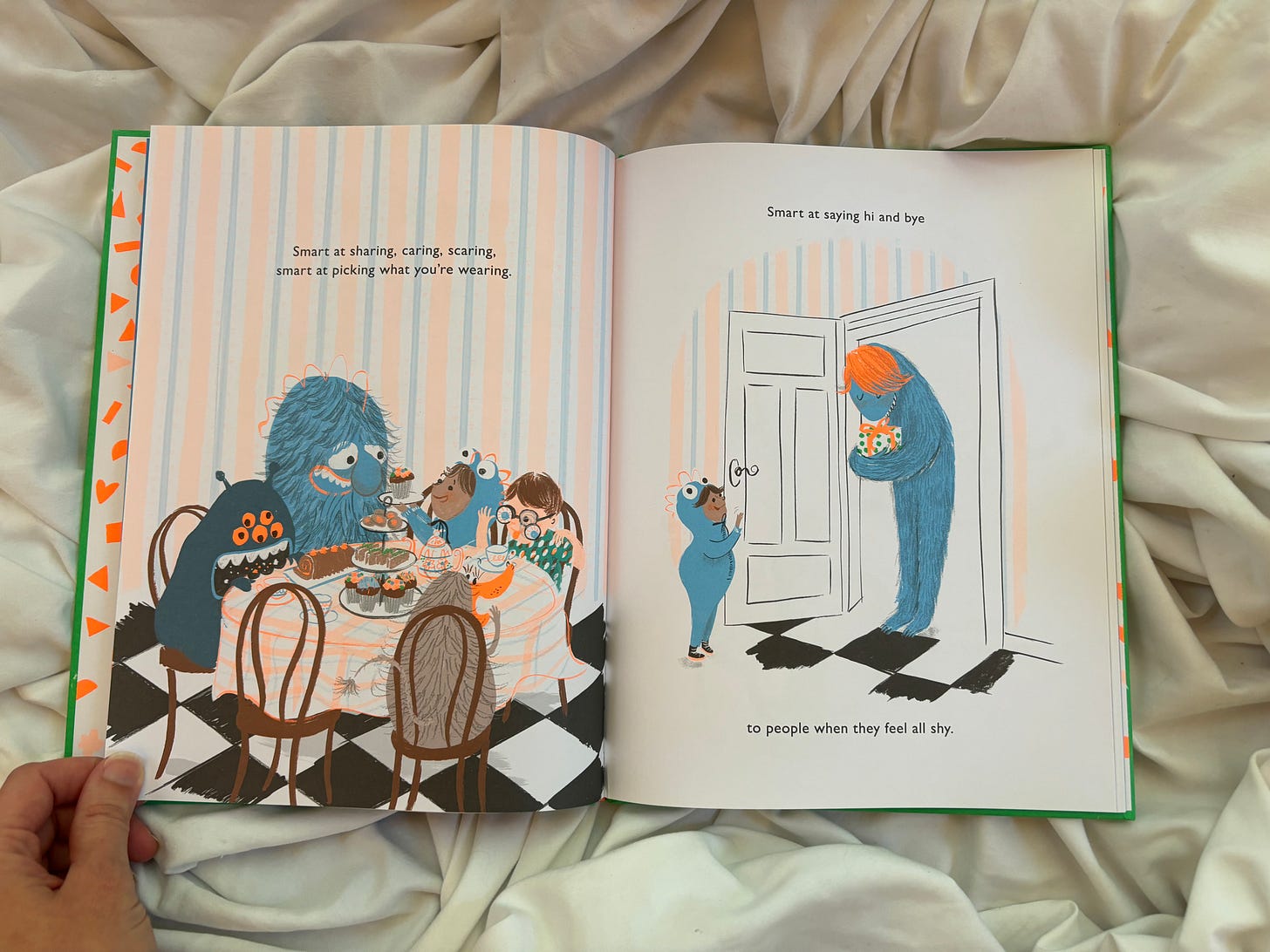

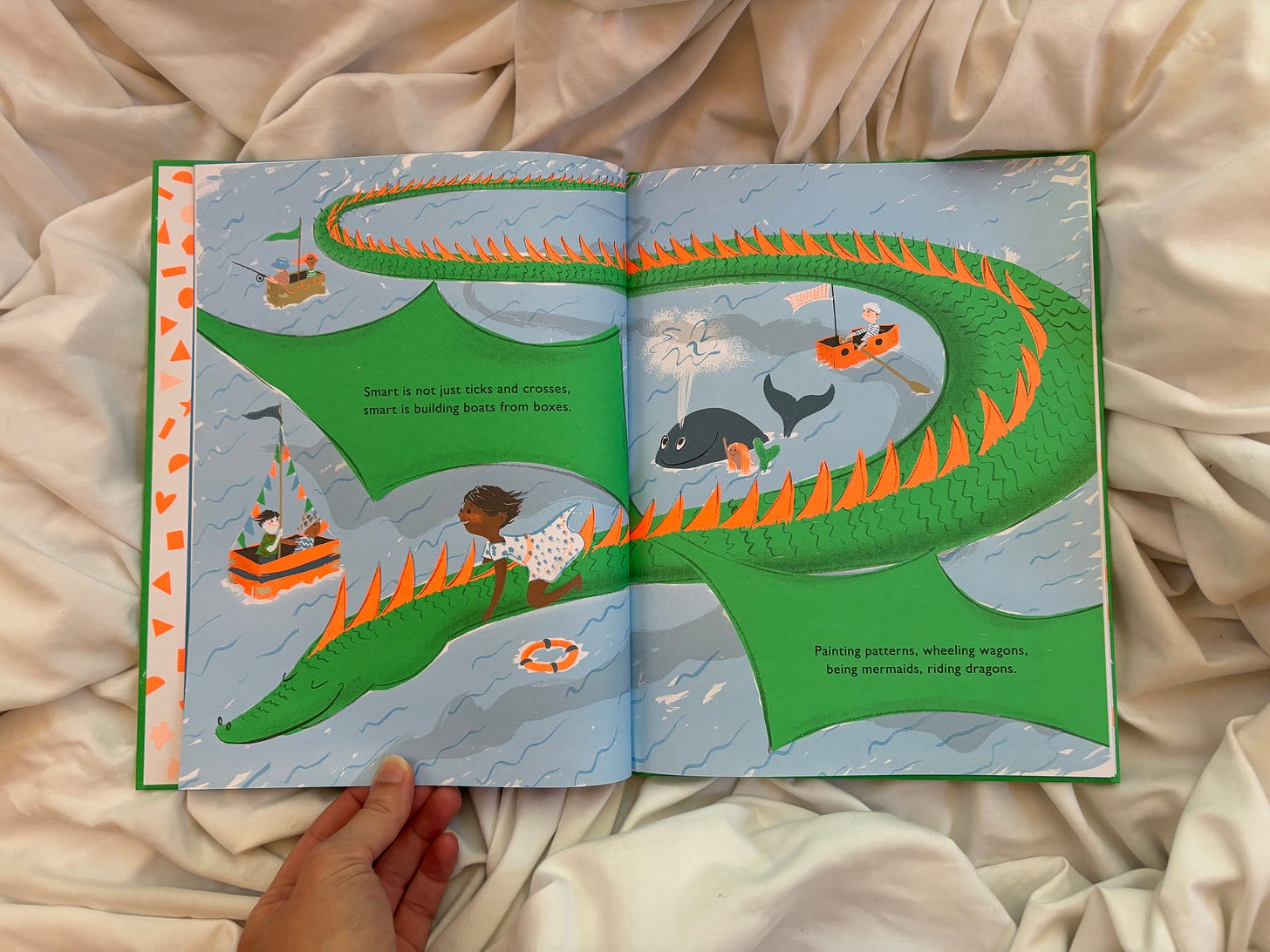

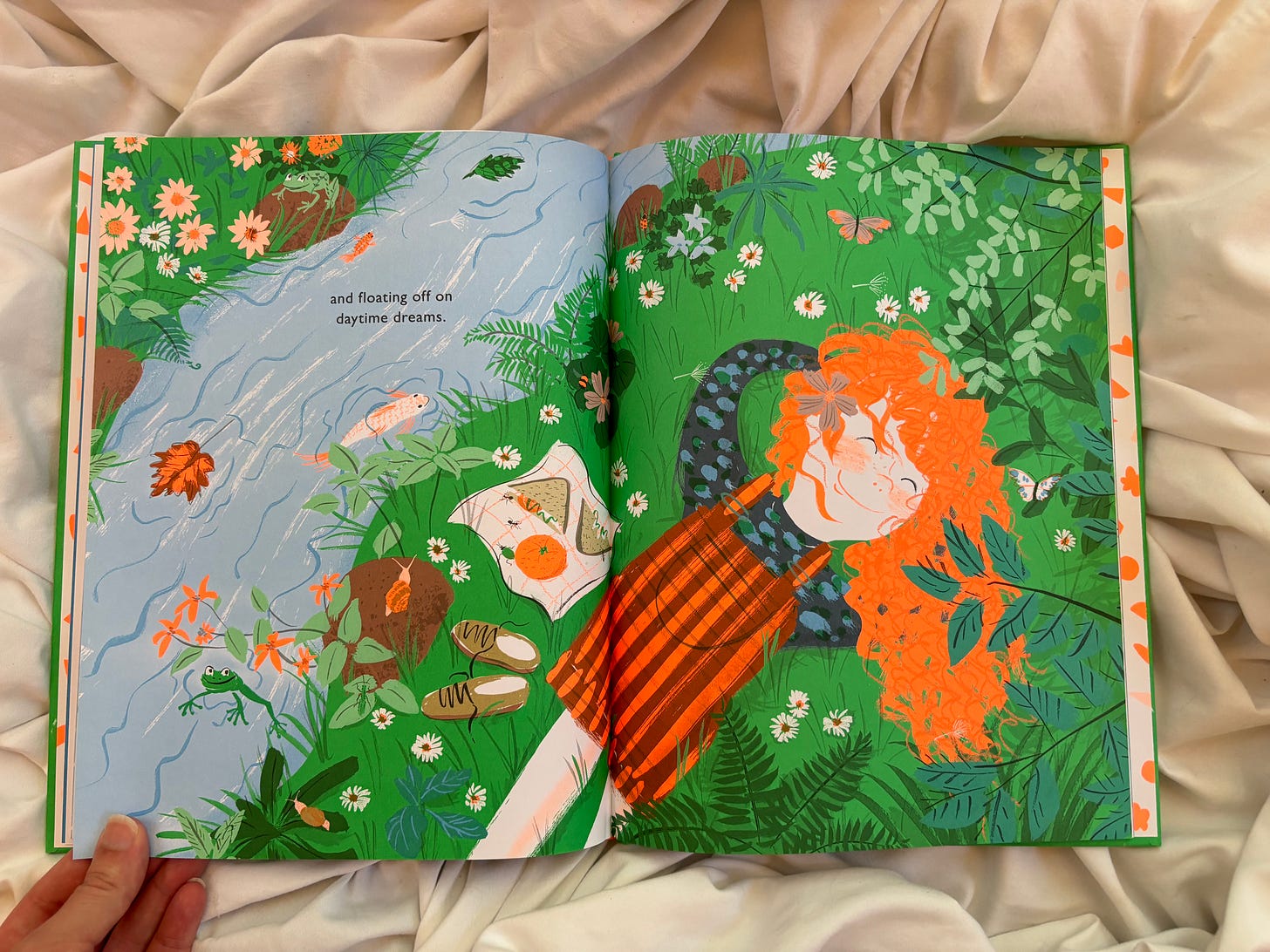

The illustrations are gorgeous, the kind of art-inspired, brand-aware, brightly creative drawings that didn’t exist very often in children’s books until millennials started writing them. They’re a next-level riff on Blueberries for Sal. They’re enchanting.

The book argues that being smart is more than just being smart at school. Here’s one example of a thing it says is smart:

I bought the book. I like the book! It’s colorful and cheery, and the illustrations are, like I mentioned, gorgeous. But I don’t think it communicates its point very well.

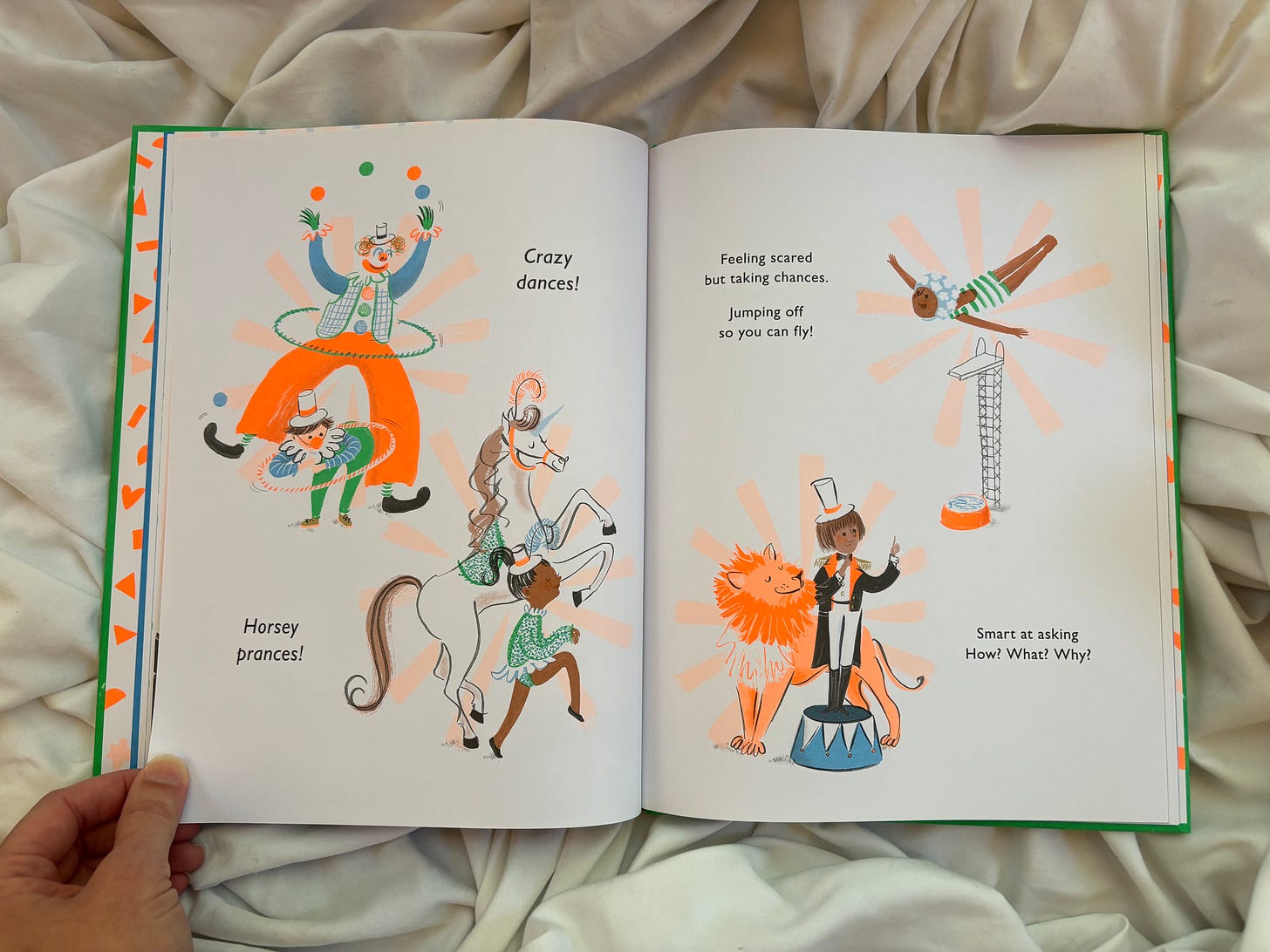

The book lists almost every way a child could spend time: drawing stars, prancing like a horse, blowing bubbles. It calls every one of those activities smart. Here’s some examples:

“Smart at drawing things with claws . . . smart is kindness when there’s crying".”

“Growing, throwing, bubble blowing. Smart is knowing where you’re going. Finding treasures, flower picking. Ukulele! Finger clicking!”

I mean, precious! But.

Most of those things aren’t actually “smart.” Not trying to be picky! Hang with me.

Most often, “smart” means academic intelligence. Sometimes it means shrewd intuition (“street smarts”) or snappy clothes (“a smart suit”). This book is interested specifically in the “academic intelligence” definition.

Our culture values school-smart smartness. Thus, “smart” is always a compliment. The value of “smart,” like the value of “beautiful,” is so widely accepted that it’s required. You’re beautiful! You’re smart!

Which is great, until we run into someone who is not beautiful, not smart. What happens when your face is pockmarked, when your essays are nonsense, when your grades never crest a C?

One option is to jump into the meaninglessness of the word “smart,” which is what this book does with aplomb. Per the book, “smart is not just being best / at spelling bees, a tricky test.” You can be “smart at sharing, caring, scaring, / smart at picking what you’re wearing.” And on and on!

There’s a second option that is, I think, better. Instead of calling everything smart, we could value other traits equally, like creativity, empathy, and bravery. Being smart at school is not the only skill you need in life. Are you good at “mixing things in mugs?”This is a sign of creativity! The ability to have fun! Maybe an early indication of a predilection towards baking! Are you good at “squeezy hugs?” This is a sign of empathy! Interpersonal physical awareness!

If the book wanted to say something important, it should have couched its argument here: every person has different skills. Although some skills and people are more frequently praised than others, every skill and person matters. You are valuable even if you cannot excel academically. There are other virtues. There are other ways to be.

You might struggle in an academic environment. Unfortunately, you still have to go to school. You will feel insufficient. Hopefully you will learn perseverance. Hopefully you will have kind classmates, helpful teachers. You might instead be bullied by classmates and belittled or ignored by teachers. School is tough! Get help from your grown-ups when you need it.

Nevertheless, you bring value to the world you live in.

That bit of nuance is powerful.

There’s a movement in the disability rights community to reexamine our cultural obsession with usefulness. Dr. Devon Price says not to use the phrase “high-functioning autism,” because there’s a value judgement attached to it: it implies that an autistic person who can drive and chat and cook is more useful than someone who needs care from other people all the time. The Puritan, individualist idea that work is a moral good and the only way to contribute to society is being sent to the cemetery, and I’m dancing at the funeral. Our cultural value system should encompass all ways of being. You don’t have to be able to hold down a job to deserve to exist in the world.

It comes back to the idea of virtue. This book accepts the superiority of “smart” whole-cloth; its entire adorable poem is based on that premise. But virtue—crucial to a healthy society, to a developing kid, to a collective conscience—is so much more than smart.

This is great, mah!

Loved!