There is something efficient about getting someone a present that’s on their wish list. You spend your coins to keep them from spending their coins on something they would buy if you didn’t. No lie, I love the efficiency of this type of gift.

But sometimes you wrap a dead battery in a scrap of paper and have Rah help you curl ribbons for it and you give it to your mom because you are three years old and she deserves a present. I did that, apparently. Mama still has it, twenty-something years later, wrapped exactly how I gave it to her. I was, at the time, offended that she didn’t open it. Little did I know, that present would be one of her favorites from me, ever.

Gift-giving is one of the most common symbolic acts we take. It requires that we slow down and imagine the world of the person we love—she stands all day at the studio, she hates hoodies but loves the one that I cut the hood off of, she doesn’t have a coffee scoop but makes a pot of coffee every morning. Then you make or find a gift that fills the space between you and them where you keep your memories and thoughts of each other.

Mama bought me a set of candlesticks a few Christmases ago. They were silver with dark twig-shaped legs and golden butterfly ginkgo leaves. They were real art, expensive, unlike the hand-me-down quality of the rest of my apartment decor. When I opened them, I was speechless.

My favorite animal has always been butterflies—probably since before I gave her the dead battery. Ginkgos have been my favorite tree since I saw one turn yellow for the first time outside Vail at Samford.

I would never have dreamed up these candlesticks. I would never have bought them for myself if I’d found them. When I opened the candlesticks, I’d never even heard of the jade butterfly variant of ginkgo trees. They’re similar to the gingko trees I’d seen, but the leaf has a split in the middle, so each one looks like a butterfly.

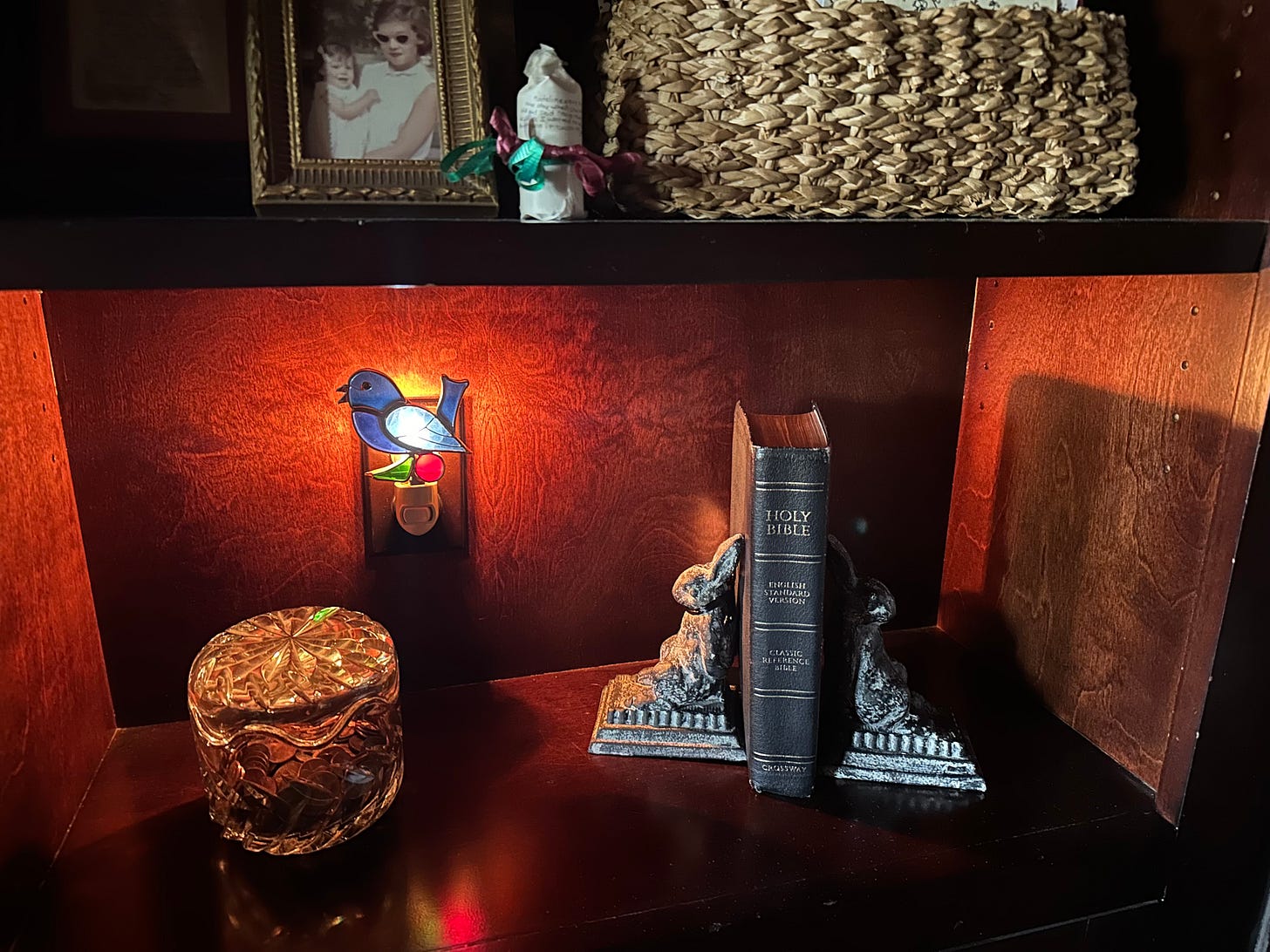

I didn’t have to know about them or find them or buy them. When I was in Chicago, twiddling around, living my own life, my mom was alive away from me, holding part of me in her—memories with me, things she’s memorized about me. She walked (into probably B.C. Clark?) and saw candlesticks that combined two things I loved and she bought them for me to express her love.

Mama has given me more gifts in her life than I’ll ever be able to count. Practical gifts, symbolic gifts, the gift of her body holding mine for ten months before I was born, the gift of her lap under my head and her arms around my waist. Hand-me-down sweatpants I didn’t want, stuffed into my suitcase (that part might have been Teddy), that I now wear! The Penderwicks books, the first time I ever read them! Monk jam in bulk! So many gifts.

Mothering is, at its core, an inefficient love. Perhaps all love is inefficient—it is quicker to eat alone than with a friend, easier to wash just your dishes, faster to never take anyone to the airport. Today, I focus on motherhood.

The inefficiencies of motherhood are almost infinite. To get lunch with a friend, you meet them inside the cafe: your friends know how to tie their shoes. And drive. Your children require you to teach them, but first to buy the shoes for them, and before that, they need to learn how to walk. It’s much more efficient to love someone who doesn’t need you to make all of their food and teach them how to balance it on a spoon. And yet, mothers are mothering.

As a mother, you decide that efficiency is not as high a priority to you as the cartwheeling creativity of a human who needs you for everything. Everything, until they don’t.

And when they move away, you’re thinking of them, and they come home for Christmas, and you buy them the most generous, gorgeous, thoughtful candlesticks. When you’re done teaching them how to walk and tie shoes and sort laundry and drive, then you show up in ways that are symbolically meaningful. You remind them that they are known, and anchored, and loved.

Mama turned sixty last July. For her birthday party, I put myself in charge of decorating the house. Her friends had all been to her home a dozen times, so I wanted it to look different from usual. I got lights, yards of fabric, chicken wire, floral foam. I love this type of thing. I wanted our home to sparkle.

I also wanted to work. To labor. I wanted to stand on a ladder, zig-zagging steel wire across the kitchen, draping pink satin and bundles of white, climbing down to squint from below and climbing back up to move the orange away from the green. It was an inefficient way to decorate the house. We did not need all this fabric, chicken wire, invisible roses. Some balloons and a cake would have worked fine. But I wanted to labor, as a symbolic act—impractical, sure, but creating beauty and symbolizing gratitude as a gift for the woman who has never stopped laboring for and loving me. What is mothering, if not practical and symbolic acts, all wrapped up in a downy hug of inefficient love.