You can hold the Internet.

Tech is virtual. When we think about it as tangible, we get more control.

I’m typing this on a new laptop. I’m working on something and just wondered about the show The Extraordinary Attorney Woo. I wanted to google it.

I didn’t.

This laptop is new! It’s sort of sacred—freshly organized, not clogged with random homework from college. I watched a video from a friendly YouTuber about where to store my files. I forgot what he said, which is what I did, so every time I need an image for a Substack post I just drag it to my desktop. But then I delete it! My new computer is for focused work, I tell myself. So I haven’t gotten on social media on this laptop—not the Facebook account I never post on, not on any of the other social media sites that let you have 3 clicks before they kick you off for not having an account. I don’t visit people.com or eonline.com or any of the other websites you go to for distraction if you don’t have social media. I don’t Google random questions. On this new computer, I focus. if I want a distraction, I have to find it in the world outside my computer—stare at the wall, grab a book, or, less holy, open my phone.

This isn’t the first time this has happened. I got a new iPhone at some point during college, and I decided that that phone would never have social media on it. No more Facebook-via-Safari. It was untouched. I wanted it to stay that way.

Both of these habit changes were practically accidental. They follow Charles Duhigg’s (cue) → (routine) → (reward) habit cycle: I ignore distractions on the Internet because a new physical item of technology (cued) me to switch my (routine) away from following distractions on the Internet. The (reward), of course, is focus, fewer hours wasted in the purgatory of limitless scroll.

This habit loop is technology-specific, and it’s the cue—a new physical item of technology—that’s interesting to me. Why is this cue so strong? Getting this new piece of hardware rewrote my habits without me even deciding I wanted to focus more. Isn’t that weird?

I think of the Internet as essentially not real. The consequences of the Internet are real—new knowledge, time wasted, both at the same time. But I can’t wrap my mind around the Internet like I can wrap my mind around an item I can also wrap my hand around.

The Internet is infinite. That’s another reason it’s hard to grasp. If you wonder where spaghetti was invented, you can Google it. You’ll have to navigate to the Internet on a device, where other tabs you’re looking at may distract you from your query. If you get past those, you can search “spaghetti” and read about it on hundreds of thousands of websites, all of which are monetizing your attention by selling ad space and data. Websites cost money to maintain, so the companies behind them add design features that grab your attention and convince you to click on articles about Italy and horse racing and the best cleaning hacks and the worst tweets. Your Internet browser has fed your brain infinity on other websites, so once you learn about spaghetti and horses and the Sponge Mama, you’re likely to stay on the Internet, where you’ll open other websites that don’t relate to your original spaghetti question at all.

This observation isn’t new, I know; everyone knows that screens are bad and addictive and blah blah blah. But take this line of thinking with me a little longer, if you don’t mind:

In the past, if you wanted to answer a question, you looked in an encyclopedia or asked the friend who was most likely to know the answer. If they didn’t have what you needed, you went to a library.

In a library, you can get distracted, but it’s different from Internet distraction. You’re motivated to find a spaghetti book because you had to travel to the library, so you’ve invested time and effort in answering your question. You might also learn about horses, but only if you physically exerted yourself to pick up a horse book. The quality of distraction is different.

I can get distracted by books, and I do, but they’re more worthy in the first place. And if I zone out, I’m not immediately bounced to something else. I just stare off for a while, then I look around and consciously decide what to do next.

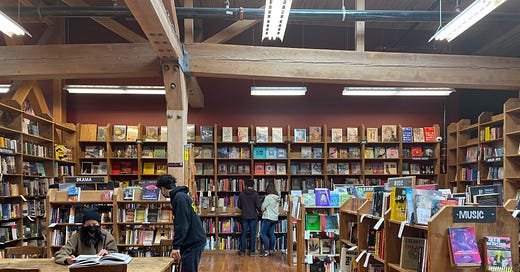

The quality of infinity in a library is different from a computer, too. Walking into a physical space crowded with shelves of books was as close to intellectual infinity as we used to get. In a library, you can’t help but think about how much knowledge is there, sure. Books on books on books. You could learn so much. You could read them all!

But actually, you can’t. I know when I go into a library or bookstore that I won’t ever be able to read every book inside. When I visit a library, I have to exercise selection. I narrow down what is essentially infinity into what can fit into my arms.

My macroeconomics professor Art Carden talked about how our minds always prefer infinity to anything less than infinity. I kept all my notes from his class (because they are life-changingly intelligent, sure, but more so because I picture myself being able to give my children a classical education from middle school through college during an apocalypse I’ve done nothing else to prepare for). I would refer to these notes to do his lecture justice but they’re 11 hours south of here and there is no apocalypse. His main point as I remember it was this: Loops of Internet-infinity ruin our ability to pay attention. And our attention is our most valuable asset.

I learned more about this idea when I read Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing. Go read the whole book! And this brief quote:

“My experience is what I agree to attend to. Only those items which I notice shape my mind—without selective interest, experience is an utter chaos.” Jenny Odell, How To Do Nothing

Also, here’s a quote from James Williams that Odell cited in How to Do Nothing. It’s from his article on Oxford’s Practical Ethics blog (here, or page 114 of Odell’s How to Do Nothing). This quotation is long, so take a pause then commit. It’s worth it:

”We experience the externalities of the attention economy in little drips, so we tend to describe them with words of mild bemusement like ‘annoying’ or ‘distracting.’ But this is a grave misreading of their nature. In the short term, distractions can keep us from doing the things we want to do. In the longer term, however, they can accumulate and keep us from living the lives we want to live, or, even worse, undermine our capacities for reflection and self-regulation, making it harder, in the words of Harry Frankfurt, to ‘want what we want to want.’ Thus there are deep ethical implications lurking here for freedom, wellbeing, and even the integrity of the self.”

And that quote reminds me of this one, from Annie Dillard: “How we spend our days, is, of course, how we spend our lives.”

My new computer cued me to stop giving my attention to things I don’t care about. I’d like to keep an eye out for other things like that.

In 2021, I watched the sun rise every day. I’d like to do the same with the sunset next year.

I have a mental map of all the gingko trees I walk by. I want to learn the names of all the trees and plants that are my neighbors.

Last Halloween, I sat in the mulch out front all evening. This is how porches felt before TVs. It’s September already and I haven’t dragged chairs out to the mulch even one time since then.

I have a ton of pictures on my phone of my feet on ground of significance or beauty. Here I am; I am grounded here. This—this is what I want to attend to.